|

|

Wildfire | Concepts | Wildfire |

|

DIMENSIONS:

|

Fire is a force of nature; it is an integral

part of life. In a forest

ecosystem, for example, trees sprout and grow for tens or hundreds

of years, then die, and fall to the forest floor.

Fire is nature’s way of cleaning up the dead so that the

living can continue to do so. Throughout history, fire has been the single most pervasive disturbance in many of the world’s forest types (Perry 1994). Any forest that experiences dry periods of sufficient length to allow fuels to dry will also burn periodically (Perry 1994).

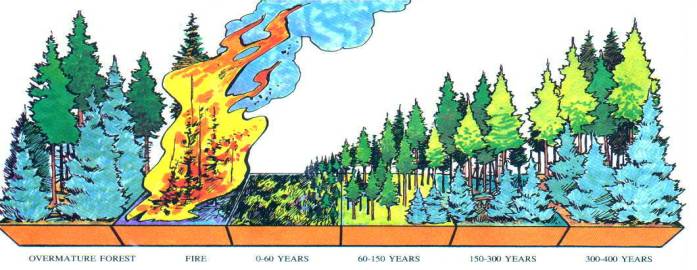

Although people often perceive fire as a

disaster to be prevented if possible, fire is a natural diversifying

agent (see figure below). Even

where large crown fires burn, fires are commonly very patchy,

killing all trees in some areas and few or none in others.

A mosaic of vegetation in different stages of succession

results, which greatly enhances landscape diversity and provides

an array of habitats for different plants, animals, and microbes

(Perry 1994). Just like other natural forces, fire will

be regarded as good or bad depending on how it affects one’s

own interests. The reason to accept the presence of fires

in Yellowstone is not because they are “good,” but because they

are intrinsic to its ecology (Franke 2000). Differences in local climate and vegetation (both affected by altitude) have caused wide variation in the fire frequency of the Greater Yellowstone Area (GYA). The fire return interval in the lower elevation grasslands of the northern range has been estimated to average from 20-25 years for about the last four hundred years (Franke 2000). However, higher elevations generally have conditions less conducive to burning (i.e. shorter growing seasons and longer periods of snowpack, cold weather, and high fuel moisture) therefore lengthening the fire return interval (Franke 2000).

|