|

|

Wildland Development | Concepts | Wildland Development |

|

DIMENSIONS:

|

Human Settlement and Economy in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem

Introduction: It is generally, and falsely, assumed

that the economy of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem is largely

based on resource use and extraction such as timber, mining and

ranching. Power (1991) completed an economic study of Idaho, Montana and Wyoming

counties that are part of the GYE, from 1969 to 1987. His data showed that the income base shifted

significantly from extraction activities to service industries

(hotels, medical centers, government, real estate, insurance,

finance) and recreation. Economic

Base Industries:

Resource extraction fell from being 25% of the wages and job base in 1969 to 1/6 of the wages, and 1/8 of the jobs in 1987, while the population, employment and total income continued to grow. (Figure 2.) Service industries grew from 53% to 62% in that same time period. These trends continue through the 1990s (see at the end of this page websites for: Census and Economic Information Center (MT), Div. of Economic Analysis (WY), Idaho Dept. of Commerce). Recreation: In Yellowstone National Park and the surrounding National Forests recreation is another important industry to the local economy, much more so than resource extraction. Based on employment, recreation is responsible for 83% of the forest-related jobs, while timber accounts for only 11%. Similarly, comparing the ecomonic value of these activities, recreation contributes over 80% on average, and timber only 5%. Non-industry wages: In addition, by 1987 only half of the personal income in the region (57 cents of every dollar) came from all labor industries combined (export, recreation, service, etc). The other half (43 cents for every dollar) comes from self-employment and, as Power puts it, “footloose” income such as retirement pensions; called so because they are not tied to any location and therefore follow its recipient. Footloose income is made up of 80% retirement pensions and 20% dividend, rent, and investment payments. These facts all point to increasing numbers of people migrating to the region. (Figure 1.)

Reasons

for sprawl: Population growth:

A guidebook for open-space conservation in Wyoming states

that from 1990-1995, the Mountain States exceeded the national

rate of growth and grew much faster as a group than did the Plains

States. Migration accounted

for about two thirds of that increase in the three fastest growing

states. Economic well-being,

including flexibility and choice of work locations in many professions,

has allowed people to migrate to areas with a perceived higher

quality of living. For

example, during the booming 1970s, the counties surrounding Yellowstone

grew at a faster rate than their neighboring counties.

Even in the depressed 1980s, the counties surrounding Yellowstone

still grew 33% faster than other counties in those same states. This willingness and ability to relocate has combined with other

social and demographic changes to create a strong incentive for

private landowners to subdivide their land and accommodate new

people while improving their own economic well being.

Land value: Several local factors have also increased the potential for land sales, subdivision and rural development. These factors include declining revenues from oil and gas and other extractive industries, and cyclical agricultural markets. At the same time, land values are increasing. These conditions create a difficult situation for some landowners, who may be land rich and cash poor. A farmer or rancher has no retirement pension. Any long term security lies solely in the equity of the operation and the ability to sell or transfer agricultural lands. Historically, that has meant passing the property to the next generation. Now, it may mean conservation easements or subdivisions. Many are faced with selling their property due to high property taxes, no heir to take over a farm, or illness that changes their ability to farm or ranch. Consequences

and Costs of Sprawl: Taken together, these

forces create an atmosphere that is conducive to land subdivision

and rural sprawl. Events which actually trigger the sale and development

of open lands may be motivated by profit or economic survival,

but are often stimulated by some type of individual or family

hardship such as health problems, lack of a retirement income,

divorce, or inter-generational tax burdens. Unfortunately, once

these factors contribute to helter skelter land subdivision, there

is often a domino effect as successive landowners cash in on their

land assets. A nearby subdivision may compromise the appeal of

maintaining a working ranch and cause other adjacent landowners

to consider subdividing their lands when they otherwise may not

have considered such actions. Yet little attention

is payed to the economic and ecologic burdens of land subdivision

and rural sprawl. Haggerty (1996) stated that conversion of agricultural

land to non-agricultural uses reduces local agricultural output,

employment, income and purchases.

Public services and infrastructure are required to meet

the needs of new arrivals. Local governments need information

that allows them to project population changes, the number of

public employees who must be hired, and the kind of public facilities

needed to serve the changing populations. For example, The Greater

Yellowstone Coalition and the Local Government Center at Montana

State University, along with county officials and local ranchers,

studied the real economic impacts of different land uses in Gallatin

County, Montana. Using simple fiscal analysis, the study showed

that "for every dollar residential property pays into local

government coffers, it demands $1.47 in direct services. Conversely,

agricultural and open space only requires 25 cents in services

for every dollar it contributes, commercial land 18 cents and

industrial land 7 cents. The study also found that over half of the local government revenues come from property taxes. It might be expected that an increase in the number of residential properties would increase the tax base and therefore increase the revenues for expenditure on improved services and possibly lower taxes at the same time. Nevertheless, according to this study and others, as more farm and range land is subdivided, the tax rates rise and the infrastructure (such as roads, schools and law enforcement) is put under greater burdens. And, local governments may be stressed by the increased demand for direct government services such as public education, road maintenance, law enforcement, noxious weed control, and others. Information

and Resources: See below for some county

and state level economic trends and forcasts in different industries.

Wyoming State Division of Economic Analysis: Largest Landowners (of 13 listed) are the US

BLM (27.9%), USFS (14.7%), State (5.7%), then NPS (3.8%).

Total federal ownership is 49%, state 5% and private is

46%. Largest Employers (of 19 listed), 7 are mining,

5 are retail trade, 2 are manufacturing, 2 are service, 2 are

TCPU (transportation, communication and pubic utilities), and

one is FIRE (finance, insurance and real estate). Labor Force and Employment forecast for 1998 – 2008 in Wyoming: The 10-year change in the number of employed is 10.8% overall, so an industry below that is decreasing its workforce, and anything above that would be increasing in employment. Services has the highest increase in labor force for the 10-years between 1998 and 2008. Services were only 2 of the largest employers, but apparently are the fastest growing. They include Grand Teton Lodge Co., and WY Medical Center Inc. Retail trade includes Hamilton Stores in Yellowstone, Mini Mart, Safeway, Sugerland Enterprises and WalMart.

Source: Wyoming Department of Employment, Research and Planning, "Wyoming's Largest Employers: June 1997, The Gems of Wyoming Industry", First Edition 1998

Montana State Census and Economic Information Center (CEIC): Park County MT: The largest industries in 1998 were services, 32.2 percent of earnings; retail trade, 14.0 percent; and state and local government, 11.2 percent. Of the industries that accounted for at least 5 percent of earnings in 1998, the slowest growing from 1997 to 1998 was durable goods manufacturing (7.4 percent of earnings in 1998), which decreased 4.7 percent; the fastest was construction (10.3 percent of earnings in 1998), which increased 6.0 percent. Gallatin County MT: The largest industries in 1998 were services, 25.3 percent of earnings; state and local government, 18.1 percent; and retail trade, 14.3 percent. Of the industries that accounted for at least 5 percent of earnings in 1998, the slowest growing from 1997 to 1998 was state and local government, which increased 3.6 percent; the fastest was durable goods manufacturing (7.0 percent of earnings in 1998), which increased 15.2 percent.

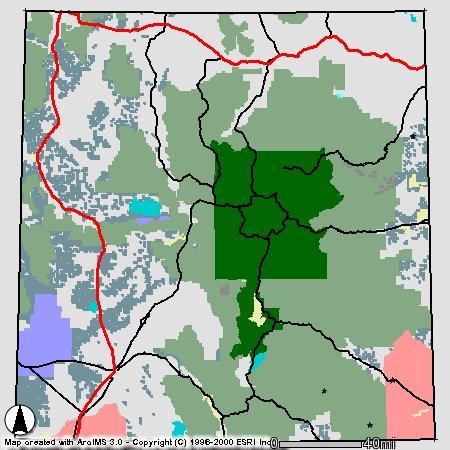

Idaho Department of Commerce: Trends in the 1990s: (Statewide data only) Services: Lodging sales revenue increased 75% between 1990 and 1998. Lodging sales trends in 1998 were strongest in southwest Idaho and weakest in north Idaho (+18.2% and -1.6%). Exports: The value of total Idaho exports increased rapidly with a 94% gain between 1990 and 1995. With a precipitous decline in semiconductor prices since 1996 and deterioration in the worth of agricultural products, there was a 29% decline in export value between 1995 and 1998. Data through September 1999 indicates a rebound in export values over the previous year in excess of 30%. Construction: Building construction value has increased by 142% between 1990 and 1998. The 72% growth in construction employment in Idaho is the sixth highest in the nation. Strength in the single-family residential market and a rebound in commercial construction resulted in a record for construction value in 1998. 1999 could show a 10% percent increase over 1998. Map

at top: maps

can be acquired from the Greater Yellowstone Area Data Clearinghouse

(GYADC). |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||